Health & safety

Flying-foxes are classified as a keystone species, given their role as pollinators and seed dispersers for tropical and subtropical ecosystems, yet the public perception of them is broadly negative. This is predominantly due to concerns about people’s loss of amenity and the potential for zoonotic diseases (diseases which originate from an animal host). The emergence of these zoonotic diseases, frequently involves active interactions between human populations and livestock or wildlife.

In the case of zoonotic diseases, data analysis has revealed a strong correlation between regions experiencing rapidly changing environments, with subsequent escalations in human-animal interactions, and disease outbreaks. Large scale habitat clearing for agriculture has drastically changed the Australian landscape, forcing flying-fox populations traditionally found in rural areas into urban areas in search of food and roosting locations. This influx of flying-foxes into human-dense areas has a number of negative impacts on bats, but most concerning to the public is the potential for zoonotic disease spill over. The two diseases which cause the main public concern are Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV) and Hendra Virus (HeV). Both of these diseases can result in human fatality and are thus treated with a high degree of caution.

The perceived notion of zoonotic disease risk presented by bats adds a further level of complexity to flying-fox conservation. A better understanding by the public of these diseases and how to minimise the risk is key to ensuring human safety and cohabitation between a very important native species and humans.

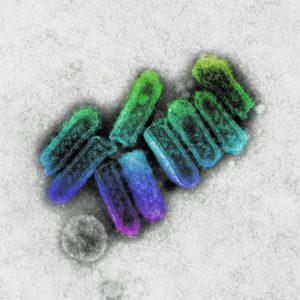

Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV)

Courtesy of CSIRO

Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV) is a neurological disease caused by a virus which presents with similar clinical signs as rabies in affected people and animals. ABLV infection in humans is very rare, but since infection causes an acute, fatal, neurological disease in humans who are bitten or scratched by an infected bat, ABLV is treated with much caution. It should be noted that there is a post-exposure vaccine which to date has been very effective.

ABLV was first detected in 1996 in a black flying-fox. Bats are the natural reservoir host of the virus with two sub lineages of ABLV identified: the yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat variant and pteropid variant. ABLV infection in bats has been reported in most states and territories of Australia, and evidence indicates an extensive geographical distribution in Australian bats. ABLV infection has been detected in all four mainland species of Australian flying-foxes and the yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat (Saccolaimus flaviventris). Infection has not been found in any other microbat species though seroconversion has been identified in a total of seven genera within five of the seven families of Australian microbats. ABLV in the Australian bat population is very low with a prevalence of less than 1%.

Transmission of ABLV is via the introduction of saliva from an infected animal by a bite or scratch, or contamination of mucous membranes or broken skin. The virus does not last long outside the host and transmission via environmental contamination is of little concern. It is assumed that all mammal species are susceptible to infection with the virus, though, experimental studies conducted on cats and dogs inoculated with ABLV seroconverted all presented with mild transient behavioral changes though there was no evidence of the virus excretion and no ABLV detected at necropsy.

To date there have been three cases of ABLV disease in humans following a bite or scratch from a bat, all of which have been fatal. The first case was a bat carer, and this was when the disease was discovered. The second was another bat carer who declined post-exposure vaccinations. The third case was, tragically, an 8-year-old boy who did not tell his parents he had been scratched by a bat.

To minimize the risk of contracting the virus, people who are bitten or scratched by a bat must receive post-exposure vaccinations. For people working with, or in close contact with, bats it is a legal requirement that they receive pre-exposure vaccinations and it is essential they use personal protective equipment and be trained to handle bats. Additionally, contact with bats and other animals should be avoided.

If you are bitten or scratched immediately wash (not scrub) the wound for at least 5 minutes with soap and running water and contact your doctor or local hospital as soon as possible.

Remember No Touch, No Risk!

For further information please read the following links:

https://wildlifehealthaustralia.com.au/Portals/0/Documents/FactSheets/mammals/Australian_Bat_Lyssavirus.pdf

http://conditions.health.qld.gov.au/HealthCondition/condition/14/217/10/australian-bat-lyssavirus

https://wildlifehealthaustralia.com.au/ProgramsProjects/BatHealthFocusGroup.aspx

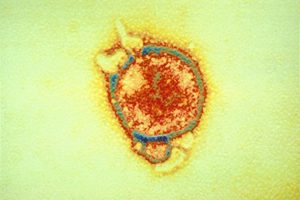

Hendra Virus

Courtesy of CSIRO

Hendra virus (HeV) is a rare zoonotic disease that can cause severe and, in some cases, fatal disease in infected horses, and in humans who have high levels of exposure to infected horses. Hendra virus is not a highly contagious disease. Close contact with the virus is required for infection to occur.

Hendra virus was first identified in 1994 during an outbreak of the disease in the Brisbane suburb of Hendra, Australia. The first identified outbreak involved 21 stabled racehorses and two humans. To date there have been a total of 7 human cases, all after high levels of exposure to infected horses. Of those 7 cases, 4 individuals died. Hendra cases have been reported in Queensland and North-East NSW most commonly during winter months.

Flying-foxes have been identified as the natural host for the virus but contrary to popular belief it is only the Black and Spectacled Flying-foxes that have been found to carry the virus. The virus has never been confirmed in Grey-headed or Little Red flying-foxes or any insectivorous bats.

Though Black and Spectacled flying-foxes may carry the virus they do not pose a risk to humans, as no human has ever contracted the virus from a bat. The virus can be detected in these two bat species throughout the year, though during winter months there is a significant spike of the virus in the Black flying-foxes, which is believed to be associated with the stress of cold weather.

The virus does not last long outside the host and is easily destroyed by the sun and every day soaps and detergents. It is believed that transmission to horses is via direct ingestion of bat bodily fluids via pastures or contaminated water.

To minimize the risk of horses contracting the disease, limit their exposure to flying-foxes. This can be done by stabling them at night and allowing some time after sunrise before allowing the horse out. There is also a vaccine now available for horses. To limit the risk to humans, isolate any infected horses from other horses and humans.

For further information please read the following links:

http://conditions.health.qld.gov.au/HealthCondition/condition/14/217/363/hendra-virus-infection

https://www.who.int/health-topics/hendra-virus-disease#tab=tab_1

https://www.business.qld.gov.au/industries/farms-fishing-forestry/agriculture/livestock/animal-welfare/pests-diseases-disorders/hendra-virus